A Sperm Whale dives off Kaikoura, New Zealand

Evolution

All members of the Order Cetacea (includes all whales, toothed and baleen) are believed to have evolved from terrestrial hoofed mammals like cows, camels, and sheep some 45 million years ago – that’s about 40 million years before man! Recent comparisons of some milk protein genes (beta-casein and kappa-casein) have confirmed this relationship and have suggested that the closest land-bound living relative of whales may be the hippopotamus. Throughout their evolution, cetaceans have become perfectly suited to an aquatic environment, and are virtually incapable of leaving it. Cetaceans illustrate an example of adaptive radiation among mammals. Adaptive radiation allows mammals as a group to effectively inhabit the land, the sea, and the air through the development of special adaptations needed to survive in each of these environments.

Members of the Order Cetacea have undergone a number of changes or adaptations needed to fare well in their watery home: their bodies have become streamlined for efficient movement through the water; their forelimbs have been modified into flippers which aid them in steering; their hind limbs have disappeared almost completely; their tail has become broadened horizontally and consists of two large flukes which propel them powerfully through the water by moving up and down, rather than side-to-side like a fish; in place of hair they have developed a thick layer of fat called blubber under their skin that insulates them from the cold and provides buoyancy; and the position of their nostrils has shifted to the top of their head creating a blowhole that allows them to effectively come to the surface for air. A whale’s blowhole generally reaches the surface before the rest of its body.

The exact evolutionary path of whales is still hotly debated but these are believed to be some of todays whales ancestors:

Pakicetus – 52 Million Years Ago

Ambulocetus natans – 50 Million Years Ago

Rodhocetus – 46 Million Years Ago

Basilosaurus – 45-35 Million Years Ago

Dorudon – 40 Million Years Ago

Janjucetus (Baleen) – 25 Million Years Ago

Squalodon (Toothed) – 15 Million Years Ago

Adapting to the Sea

In addition, a number of other changes have taken place to help whales adapt to life in the sea. Many of these changes are related to the position and abilities of their sensory organs, as life in the water is not the same as life on the land. Sound and light travel differently in water than they do in the air. As a result, whales have developed unique ways of hearing and seeing. Hearing in particular is highly developed in whales, so much so that they depend on it in the same way that we depend on the combination of our eyes, ears and nose to understand the world around us. Many of the whale’s sensory and reproductive organs have been internalized to reduce drag while swimming. For example, whales do not have external ears, but rely on an internal system of air sinuses and bones to detect sounds.

Changes in their reproductive and parental behaviours have also taken place, enabling whales to provide optimum care for their young in the cold, large ocean. Along with these differences, cetaceans do, however, possess many of the same physiological systems such as circulatory, digestive, respiratory, and nervous systems as the land mammals from which they evolved. For instance, many species possess multi-chambered stomachs even though there is no obvious advantage to having such an arrangement as whales do not chew cud!

Some acrobatics from an Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin shows their streamlined shape

The Humpback Whale

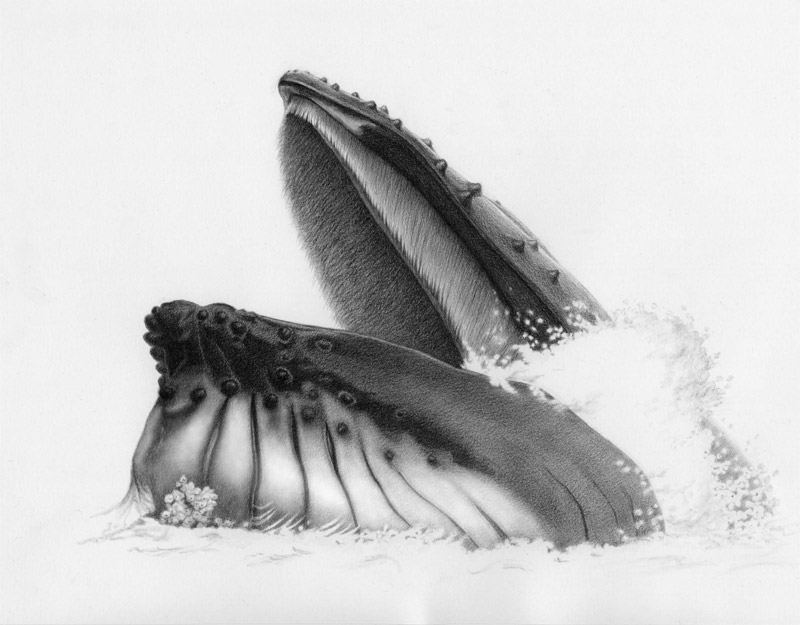

The head of a humpback whale is broad and rounded when viewed from above, but slim in profile. The body is not as streamlined as other rorquals, but is quite round, narrowing to a slender peduncle (tail stock). The top of the head and lower jaw have rounded, bump-like knobs, each containing at least one stiff hair. The purpose of these hairs is not known, though they may provide the whale with a sense of “touch.” There are between 20-35 ventral grooves which extend slightly beyond the navel.

A Humpback Whale by Sharon Salmi

Adult males measure 12.2 to 14.6m; adult females measure 13.7 to 15.2m. They weigh 22,000 to 36,000kg. Their scientific name is Megaptera noveangliae. This means “giant wings”, which refers to their large front flippers that can reach a length of 4.6m or about one-third of the animal’s entire body length. The body is black on the dorsal (upper) side, & mottled black and white on the ventral (under) side. This colour pattern extends to the fluke (tail). When the humpback whale sounds (goes into a long or deep dive) it usually throws its fluke upward, exposing the black and white patterned underside. This pattern is distinctive to each whale. The flippers range from all white to all black. The shape & colour pattern on the humpback whale’s dorsal (top) fin & fluke are as individual in each animal as are fingerprints in humans.

A Humpback Whale Tail

Humpbacks have become renowned for their various acrobatic displays. In fact, the common name “humpback” refers to the high arch of their backs when they dive. About 2/3 back on the body is an irregularly shaped dorsal fin. Its flippers are very long, between 1/4 and 1/3 the length of its body, & have large knobs on the leading edge. The fluke, which can be up to 5.5m wide, is serrated and pointed at the tips.

A Humpback Whale Breaches

One of the humpback’s more spectacular behaviours is the breach. Breaching is a true leap where a whale generates enough upward force with its powerful flukes to lift approximately 2/3 of its body out of the water. A breach may also involve a twisting motion, when the whale twists its body sideways as it reaches the height of the breach. Researchers are not certain why whales breach, but believe that it may be related to courtship or play activity. Some behaviours such as headlunging, which occurs when one whale thrusts its head forcefully towards another whale in a threatening manner, are believed to be aggressive behaviours meant to ward off competitors. Males display this behaviour most often to gain access to females.

A Humpback Whale Peck Slaps

Many other behaviours including fluke (peck) slaps, flipper slaps, and headslaps have also been characterized, although their apparent functions are unknown. At least 3 different species of barnacles are commonly found on both the flippers and the body of humpback whales. It is also home for a species of whale lice, Cyamus boopis.

Communication

The “songs” of humpbacks are made up of complex vocal patterns. All whales within a given area and season seem to use the same songs. However, the songs appear to change from one breeding season to the next. Scientists believe that only male humpbacks sing. While the purpose of the songs is not known, many scientists think that males sing to attract mates, or to communicate among other males of the pod.

The Pod

A Pod refers to a social group of whales. Humpback whales typically belong to pods consisting of 2-3 individuals, although pods as large as 15 individuals have been sighted. Scientists feel that whales belong to certain pods for relatively short periods of time. One type of pod that is especially interesting is the cow-calf pod. A cow-calf pod represents the longest association between individual whales. In this type of pod, the mother whale, the cow, remains with her calf for a year during which time she nurses the young whale. In many instances, cow-calf pods are accompanied by another adult known as an escort. Escorts can be of either sex, but are most often reported to be males. Escorts do not remain in the cow-calf pod for long periods of time, usually for only a few hours. There have been no reported sightings of whale pods which contain more than one calf, indicating that each young whale is given a great deal of individual attention and care. This fact, together with the fact that the normal breeding-cycle of a humpback whale is two years, helps to explain why recovery of humpback whale populations progresses so slowly.

A Pod of Humpback Whales (LtoR Male Escort, Calve and Mother

World Range & Habitat

Humpback whales are found in all of the world’s oceans, although they generally prefer near shore and near-island habitats for both feeding and breeding. The current world population for the species is estimated to be around 60,000 individuals 6,000 to 8,000 in the North Pacific, 12,000 in the North Atlantic, and approximately 40,000 in the Southern Hemisphere) or about 30-35% of their original population before whaling, and can be divided into groups based on the regions in which they live. In the Atlantic, humpbacks migrate from Northern Ireland and Western Greenland to the West Indies (including the Gulf of Mexico).

A Pod of Humpback Whales in their feeding grounds in Antarctica

Feeding Behaviour (Ecology)

Humpback whales feed on krill a small shrimp-like crustaceans, and various kinds of small fish. Each whale can eats up to 1,300 kg of food a day. As a baleen whale, it has a series of 270 to 400 fringed overlapping baleen plates that hang from each side of the upper jaw where teeth might otherwise be located. These plates consist of a fingernail-like material called keratin that frays out into fine hairs on the ends inside the mouth near the tongue. The plates are black and measure about 76cm in length. During feeding, large volumes of water and food can be taken into the mouth because of the pleated grooves in their throat which allow for enormous expansion. As the mouth closes, water is expelled through the baleen plates, which trap the food on the inside near the tongue to be swallowed. This efficient system enables the largest animals on earth to feed on some of the smallest. They are also known to concentrate the food by forming a bubble curtain, created by releasing air bubbles while swimming in circles beneath their prey.

A Feeding Humpback Whale by Teresa Byrne

Life History

Humpback whales mate during their winter migration to warmer waters, and eleven to twelve months later, upon their return to winter breeding grounds. They reach sexual maturity at 6-8 years of age or when males reach the length of 11.6m and females are 12m. Each female typically bears a calf every 2-3 years and the gestation period is 12 months. A humpback whale calf is between 3 to 4.5m long at birth, and weighs up to 907kg. It nurses frequently on the mother’s rich milk, which has a 45% to 60% fat content. The mother must feed her newborn about 45kg of milk each day for a period of 5-7 months until it is weaned. The calf is weaned to solid food when it is about a year old. After weaning, the calf has doubled its length and has increased its weight 5 times, attaining a size of about 8.2m and 9,072kg. The maximum rate of reproduction for the species is one calf per year, but this is seldom practiced as it puts quite a strain on mother whales. Scientists estimate the average life span of humpbacks in the wild to be between 30-40 years, although no one knows for certain, yet.

Migaloo – The White Whale

Migaloo is a white humpback whale that was first observed in 1991 off Byron Bay when it was estimated to be 3-5 years of age. In most years since then it has been recorded undertaking the winter migration into eastern Australia. In addition to sightings in Tasmania, Victoria and New South Wales, Migaloo has been seen in New Zealand waters. In 1998 and 2003 Migaloo was recorded ‘singing’, indicating that it is an adult male.

In August 2003 when he was 15-17 years of age, he was hit by a sail-boat off Townsville. He received a small wound & associated abrasions.