Humpbacks are probably one of the most famous of all the whale species, known for their acrobatic displays, singing and epically long migrations across the worlds oceans. I don’t think there is anything more joyful than watching a Humpback calf hard at play. Just imagine a four ton Labrador puppy and you kinda get what I mean.

Common Name: Humpback Whale

Other Names: Merry Whales

Scientific Name: Megaptera novaeangliae

Conservation Status: Vulnerable/Endangered

Length: New-born calf 4 metres, Adult Females 16 metres, Adult Males 14 metres.

Weight: Birth weight is about 2 tonnes. Adults weigh up to 50 tonnes.

Gestation: 11 months

Weaning Age: up to 11 months

Calving Interval: 2 to 3 years

Physical Maturity Age: 12 to 15 years

Sexual Maturity Age: 4 to 10 years

Lifespan: 60+ years

Mating Season: June to October

Calving Season: June to October

Cruising Speed: 8km/h

Protected Since: 1965

Field Identification

– Dark grey in colour with white markings.

– Very long pectoral fins with bumps along the leading edge – longest pec fins of all the whales.

– Bushy shaped blow from two blow holes.

– Small stubby dorsal fin two thirds of the way along their backs.

– Tail fluke markings and colour individual to each animal (like a human fingerprint) and used to identify each animal. May raise tail when deep diving.

– Slim head or rostrum covered knobs and throat groves underneath.

– Highly acrobatic – often seen breaching, slapping tail and pec fins, spy hopping.

Taxonomy

Humpback whales are members of the rorquals family (genus Balaenoptera) which also includes the Blue, Fin, Bryde’s, Sei and Minke whales. Recent DNA studies indicated that Humpbacks may actually be more closely related to certain rorquals, particularly the Fin whale (B. physalus) and possibly the Gray (Eschrichtius robustus) than it is to others such as the Minke.

The common ‘Humpback’ name is derived from the curving of their backs when diving. The scientific name Megaptera come from the Ancient Greek mega- μεγα (“giant”) and ptera/ πτερα (“wing”), in reference to their large peck fins.

Recent genetic research by the British Antarctic Survey in 2014 confirmed that the separate Humpback populations of the North Atlantic, North Pacific and Southern Oceans are more distinct than previously thought. Some biologists argue that these populations should be regarded as separate subspecies and that they are evolving independently. This is still hotly debated!

Description

The humpback whale is one of the larger rorqual species of baleen whales. Famed for their spectacular acrobatic displays and singing they were once called the Merry Whales.

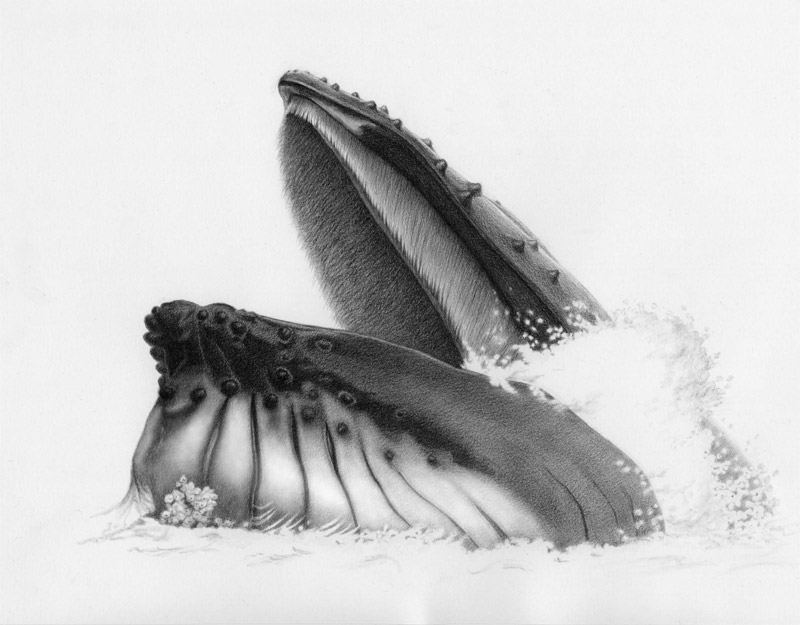

Humpbacks have a very distinctive body shape with a knobbly head, distinct throat groves, small dorsal fin and the longest pectoral fins of any of the whale species, which can be up too a third of their body length.

The maximum recorded length of a Humpback is 17.4 m, through females are generally no more than 16 metres in length and they are normally 1–1.5 metres longer than the males. Southern Hemisphere Humpbacks whales generally have a greater degree of white colouration on their sides, tummies and undersides of their pectoral fins and tails than Northern Hemisphere Humpbacks. Their dorsal fin is very distinctive from other balaenopterid whales as they have a hump on its leading edge.

A distinctive feature of a Humpbacks head and lower jaw are the bumps or knobs called tubercles, each contains a single hair follicle. The purpose of these is still not really understood but it is believed that they may act as part of the whales sensory systems. The rostrum is generally flat leading back to the raised splash guard infant of the blowholes. Ventral grooves that allow the throat to expand massively whilst feeding run from the lower jaw to the umbilicus, about halfway along the underside of the body. These grooves are less numerous (usually 14–22) than in other rorquals, but are fairly wide. Humpbacks have 270 to 400 darkly coloured baleen plates on each side of their mouths. These plates measure from 46cm in the front to about 91cm in the back of the mouth.

Humpbacks have the longest pectoral fins of any of the whale species and from where they get their scientific name ‘Giant Wing’. These long peck fins are one of the easies ways to ID a Humpback. The large length peck fins greatly assist the whales manoeuvrability. They also have large ‘bumps’ on their leading edge which scientists discovered improve its aerodynamics further enhancing manoeuvrability. The fins large surface area may also be helpful for body thermo regulation. Humpbacks will often bang their peck fin on the waters surface, this may be for fun, to communicate or in attack/defence.

Another distinguishing feature of Humpbacks are the unique markings on the underside of the tail flukes. These markings are like human fingerprints, no two are the same and allow scientists/researchers to identify individuals whales.

Distribution

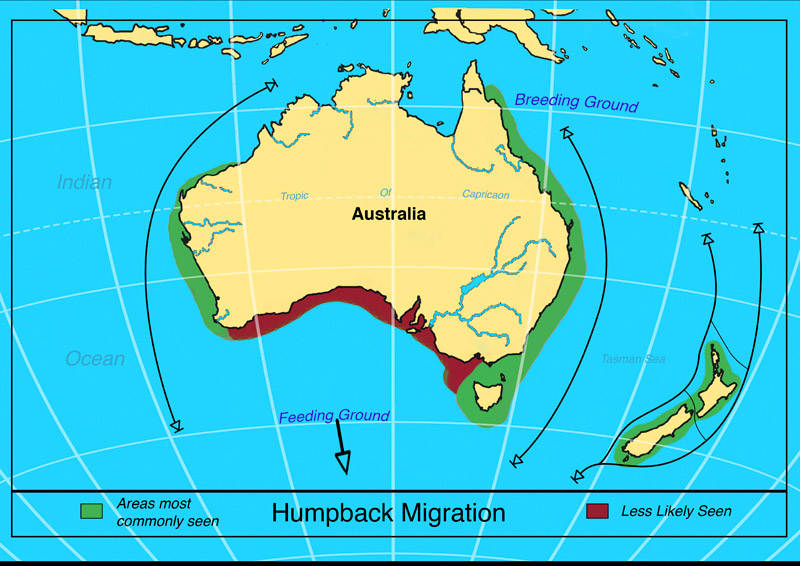

Oceania – There are three distinct Humpback populations and migration routes in Oceania, the Western Australian (Group 10), the Eastern Australian (Group 11) and Oceania (New Zealand, South Pacific) (Group 12). The whales make one of the longest migrations in the animal kingdom from summer feeding grounds deep in the Southern Ocean to their winter breeding grounds in the tropical waters off Western Australia, Queensland and into South Pacific. The migration along the Australian coasts is primarily in coastal waters less than 200 metres deep and generally within 20 km of the coast.

The east coast breeding grounds are along the Queensland coast and the Great Barrier Reef with important rest areas such as Hervey Bay along the way. Some whales are believed to carry on out into the Coral Sea as far as New Caledonia. Recently with the spotting of Migaloo (the all white Humpback) off New Zealand and then off Queensland during the northern migration it is thought that there might be much greater mixing of the Eastern Australian and Oceania groups than first thought.

On the west coast Humpback whales travel north to major breeding grounds such as Camden Sound off the Kimberly Coast. This appears to be the northern most limit for the majority of the west coast whales although Humpback whales are often sighted as far north as Ashmore Reef. During the southern migration whales there is evidence that whales may be breaking away from the coastal migratory route and heading offshore from the coast between Exmouth and Shark Bay.

Global – World wide there are fourteen distinct humpback population groups that are isolated from one another and severely fragmented. Due to the seasonal nature of their migrations Northern and Southern Hemisphere populations never meet. Whilst Australia’s west and east coast humpback whale populations are currently considered genetically distinct analysis of Humpback song has shown links between the west and east coast populations and has confirmed links between east Australia, New Zealand, New Caledonia and the Pacific Islands populations.

Humpbacks are listed as endangered worldwide, with the Northwest Africa and Arabian Sea populations in particular trouble.

1. West Indies

2. Northwest Africa (Cape Verde Islands) – Endangered

3. Western North Pacific – Threatened

4. Hawaii

5. Mexico

6. Central America – Threatened

7. Brazil

8. Southwest Africa (Gabon)

9. Southwest Africa (Madagascar)

10. Western Australia

11. Eastern Australia

12. Oceania

13. Southeastern Pacific

14. Arabian Sea – Endangered

Population

The recovery of the Australian Humpback whales from the brink of extinction is one of the great success stories of modern conservation. Both the Australian west coast and east coast populations are recovering from near collapse caused by whaling during the 1950s and 1960s. When whaling finally ceased it is estimated that there were less than 500 Humpbacks were left in the east coast. It is thought that a population increase of between 10–11% for the east coast and and from between 9.7–13% for the west coast population per year is the highest in the world indicating that both populations are increasing at, or above, maximum rates possible. It is estimated that the east coast population is now close to 40,000 whales.

Humpback Migration

Humpback Whales undertake some of the most epic migrations in the animal kingdom. The simply reason they do this is because their rich feeding grounds are in deep in the freezing waters of the Southern Ocean off Antarctica. Humpback calfs are born without the thick insulating bubble layers the adults have to protect themselves from the cold. So the whales must move to warmer tropical waters to give birth.

In Oceania there are three distinct migration populations, the Australian west and east coasts and Oceania (New Zealand, South Pacific). All of these groups feeding grounds are in the Southern Ocean off Antarctica. The northern migration starts in late autumn (May) through to August with the whales moving from the Southern Ocean north to their various breeding grounds. Mating occurs along the way as well as in the breeding and rest areas.

It was long believed that the Humpbacks did not feed during the migration but more and more evidence of opportunistic feeding has been discovered.

The Australian West Coast Population – Off the Western Australia the Humpbacks travel north hugging the coast to their breeding grounds off the Kimberly region. Some whales travel through the Great Australian Bight before heading up the west coast with everyone else. The majority of whales will be within 25km of the coast in shallow water.

Many important rest areas have been identified such as Augusta, Geographe Bay, Shark Bay, Exmouth Gulf and the southern Kimberley region. There are several other areas that the whales may also use including the Houtman, Abrolhos, Montebello and Barrow islands.

The western Australian population major breeding areas have been identified in the Kimberley region, particularly between Lacepede Islands (16.8° S) and Camden Sound (15.38° S). Camden Sound also appears to be the northern most limit for most whales.

On the west coast opportunistic feeding has been observed at Augusta and off Point Cloates.

The Australian East Coast Population – The eastern Australian Humpbacks also swim north close to the coast so they avoid swimming into the southward flowing Eastern Australian Current. Three major aggregation areas have been identified in Queensland, around the southern end of the Great Barrier Reef, Hervey Bay and off the Gold Coast.

The exact locations of the breeding grounds on the east coast are still unknown but thought to be between central and northern Queensland within two possible locations within the southern Great Barrier Reef region: east of Mackay; and further south in the Capricorn and Bunker island groups off Gladstone.

On the southward migration the whales use the Eastern Australian Current to their advantage with the bulk of the adult whales using it as a free ride south. The mothers and newborn calf hug the protected coastal waters as the mothers teach their newborns to swim and fatten them up ready for the cold of the Southern Ocean. It is believed that as many as 30% of the eastern population may use Hervey Bay as a resting area.

Opportunistic feeding has been observed along the migration route off Fraser Island in Queensland and close to shore off Eden, NSW from September until November.

The Oceania Population – The third Oceania Group migrates from the Southern Ocean north past New Zealand and into the South Pacific.

This migration path is far more exposed with vast stretches of open ocean for the whales to contend with. There is also evidence that some whales may cut across the Tasman Sea from southern New Zealand to join the Australian East Coast migration. In New Zealand important rest areas such as Kaikoura, Hauraki Gulf, The Bay of Islands, Marlborough Sounds and the Bay of Plenty.

Important breeding grounds are found amongst the islands of the South Pacific such as the island chain of the Kingdom of Tonga.

Antarctica – The rich waters of the Southern Ocean abound in life and it is here that the Humpbacks go in search of the huge upwellings of Krill.

Over the summer months along the southern boundary of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current Humpbacks will be found gorging themselves on the densest concentrations of Krill they can find. This generally occurs south 55° and for the western population between 70° E and 130° E and between 130° E and 170° W for the east coast population. The Balleny Islands off Antarctica has been identified as a very important and productive feeding ground for the east coast Humpbacks.

Behaviours

Humpback whales are natural show-offs! They seem happy to entertain whale watchers by breaching; spy-hopping; lobtailing and flipper-slapping. Hardly surprising that humpbacks are the most popular whales on whale watch trips, and probably create more great photo opportunities than any other cetacean species. Their dives usually last less than 10 minutes but can be up to 45 minutes long. Males can be quite aggressive towards each other during the breeding season and they sometimes have scars on their skin from fighting.

Song

Humpbacks are famous for their singing! Humpbacks produce a variety of sounds throughout their habitat range. These sounds can be part of feeding/foraging, communication and other social situations. The most famous sounds they make are the songs produced by solitary males. These songs can last a few minutes to hours and over a range of frequencies from less than 20 Hz to 8 kHz. It is believed that these songs form an integral part of male mating displays and behaviours. Recently what is believed to be feeding songs have been recorded Southern Ocean Antarctic feeding grounds.

Feeding

Fish, krill and/or other crustaceans.

Humpbacks feed by taking a large mouthful of water and food such as Krill. They then push the water out of their mouths using their tongues. Their mouths contain baleen plates which filter out the food which can then be swallowed.

Humpbacks have also developed a unique way of working together to feed know as Bubble Feeding. To do this they deep dive together then swim back to the surface in a corkscrew pattern releasing bubbles as they do. The bubbles form a net that scares and concentrates the prey into a tight space which they can all take a huge mouthful of as they reach the surface.

Life Cycle

Humpback calfs are born after a gestation of 11 to 12 months, measuring up to four metres and several tons in weight. Lactation extends over 10 to 12 months although some calfs have been observed independently feeding at six months of age. Sexual maturity is reached between four and eight years with a life expectancy of at least 50 years, perhaps significantly longer. Humpback calfs are particularly vulnerable to predation by the Killer Whales and large sharks.

Threats

Like all marine mammals Humpbacks Whales have a number of natural and man made threats. Tragically the biggest treat to them is mankind and our activities such as whaling, pollution and climate change.

Natural – Given they’re large size adult Humpbacks Whales have few natural predators. Young, sick, injured and old whales may be attached by Killer Whales and sharks.

Man Made – Pollution, climate change, acoustic disturbance, ship strikes, entanglement and bycatch, over-harvesting of food sources such as Krill stocks and habitat destruction.

Whaling – World wide Humpbacks Whales were decimated by commercial whaling. So much so that by the late 1950’s there were so few whales left that whaling became uneconomic to continue. Officially commercial whaling of Humpbacks ceasing in 1963 although Illegal may have continued until the 1970’s. Commercial whaling is currently suspended by the International Whaling Commission (IWC). The IWC can issue special permits for Minke, Fin, Sei, Sperm, Bryde’s and Humpback whale species as part of lethal ’scientific’ whaling research programs undertaken by IWC members which include Iceland, Japan, Norway and the Republic of Korea. To date no Humpbacks have not been caught under Special Permit whaling. Japan left the IWC in late 2018 and resumed commercial whaling in 2019.

References/Sources

Australian Department of the Environment, Canberra

NSW Department of the Environment

QLD Department of the Environment

NZ Department of the Environment

Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises by Mark Carwardine

Whales, Dolphins & Seals: A Field Guide to the Marine Mammals of the World by Hadoram Shirihai and Brett Jarrett

Copyright 2020 David Jenkins – Whale Spotter